At a speed of two hundred: where the fastest trains on the planet are rushing. At a snail's pace How fast does a regular passenger train travel?

Now I’ve once again started talking actively about the HSR - the high-speed (rail) line Moscow-Kazan. Apparently, active development of the project has begun. Well, no one has seen the project yet (only rough sketches), I think there will be specifics soon, but for now I’m interested in another question - what are the speeds there in general and how are things going with train speeds in general. Well, that is, let’s say there is Sapsan - a fairly fast electric train (the essence is an electric train), but it is not classified as high-speed. And there is the “Nevsky Express” - an ordinary train with passenger carriages, driven by a locomotive that travels the route from Moscow to St. Petersburg a little slower than Sapsan...

In short, for me personally, the speed of the train was some unknown number, despite the fact that, as a rule, the trains move exactly according to the schedule (there are minor deviations, of course, but for the most part everything is on time, and even if I fell behind somewhere, they can catch up later). In short, I wanted to figure out how things are going with the real speed of trains (and what prospects there are in general).

Perhaps we should start with the fact that in the characteristics of locomotives/(electric) trains two numbers are usually indicated: design speed and long-term speed (less often, hourly speed). The first is, roughly speaking, the speed, the maximum permissible without compromising operation (in theory, it is probably possible to accelerate faster, but the impact on engines, on rails, etc. is greater - in short, they try not to raise it higher, so as not to violate operating conditions). The second one is a little more difficult. Roughly speaking, the continuous speed is the indicator at which electric motors can operate most efficiently for a long time (the minimum speed at which you can drive for a long time at maximum traction position). In short, both numbers are essentially technical, having an indirect relationship to reality.

If we talk about locomotives/trains from a practical point of view: getting from point A to point B, then it would be more correct to talk about commercial speed (it is also called route speed or average daily speed). Generally speaking, it is different for each train, for example, two trains with different commercial speeds can have the same traction locomotives, the same cars and run along the same track (by the way, this speed is affected by stops along the way). For example, we travel from Saratov to Moscow on train No. 009, and we cover the 865-kilometer journey in 14 hours 35 minutes (we get an average speed of approximately 59 km/h). If we leave a little later, on train No. 017, we will cover the same route in 15 hours 26 minutes, and the speed will already be 56 km/h. At the same time, the cars are the same, the traction locomotives are the same (4 different locomotives from Saratov to Moscow).

Actually, based on their speed, all trains can be divided into the following groups:

- passenger (route speed less than 50 km/h)

- passenger ambulances (route speed not lower than 50 km/h)

- high-speed passenger (route speed not lower than 100 km/h with permissible speeds in the range of 141-200 km/h;)

That is, both the 9th and 17th trains, by all indications, are fast, although they do not move much faster than passenger trains, and the locomotives driving these trains allow them to move at speeds close to high-speed ones. Technically, as I understand it, nothing prevents us from abandoning slow passenger ones and switching to fast ones (and actively developing into high-speed ones). Now the locomotive fleet is being actively updated, and the cars and rails (with other infrastructure) are no longer the same. The problem, as I understand it, is in the dispatching/schedules of trains, which were compiled back in Soviet times (in the early 80s) to suit the technical capabilities of that time. That is, for good reason, it is necessary to change timetables globally, but this is serious work, so for now they are limited to some individual priority routes (where, by the way, high-speed trains appear), but for the most part they are not touching them yet:

Accordingly, most of the passenger trains plying the expanses of Russia at the moment are either just “trains” or slightly more nimble “fast trains”. Even the ambulances can’t be said to be very fast, but they are much cheaper than traveling by plane and more comfortable than traveling by bus/car (this is of course debatable, but in general the quality of passenger carriages is now improving). By the way, the concept of route speed applies mainly to long-distance trains. There is a large class of commuter trains with frequent stops, small gaps between stations, and where, as a rule, multiple unit rolling stock (MURR) is used - often electric trains, less often motrices). Well, these can also be reached, if desired, from one large city to another (though with less comfort) and much more slowly - according to this classification system, they are more likely to be classified as “trains” (although some sections may fall under the class of “fast”), with that a standard electric train can accelerate to 120-140 km/h without risk.

Nevertheless, if we start talking about “high-speed trains” (that which travels on average more than 100 km/h), then the first thing that comes to mind is electric trains - MVPS (and not only here - the situation is the same in other countries). It turns out that at the moment (high) speed trains are trying to compete not with regular long-distance trains, but with aviation. Usually here they take distances within 1000 km (at least I have heard such a figure more than once). Accordingly, at high speeds over relatively short distances, all these compartments are no longer needed for long trips - you just need comfortable seats (and in such situations, you can seat more people in one carriage). But the main thing is the presence of a large number of motorized axles allows you to have a higher specific power (the ratio of engine power to the mass of the rolling stock), which allows you to obtain high accelerations and high speeds. That is why the development of high-speed railway transport is primarily taking the MVPS route (the essence is “electric trains”):

In the USSR, the topic of high-speed railway transport was not only not given due attention, but the tasks were different and more serious. The first Soviet MVPS - ER200 was developed at the Riga Carriage Works in 1973, then it was tested for a long, long time, but its commercial operation (on the Moscow - Leningrad section) began only in 1984, when it was already obsolete. Perhaps this is all that they were able to implement in practice in the USSR; RVR somehow completely deflated after the collapse of the USSR...

In Russia, already in the 90s, they began to try to cut their own modern high-speed train project, which resulted in the ES-250 (Falcon) - in practice, an even less successful model (compared to the ER200) - things did not go further than trial runs/tests.

In general, then it became clear that the issue of high-speed (and in the future - high-speed) railways could not be solved on our own - the backlog was too significant, we could probably catch up, but how many years would it take - wouldn’t it be easier to start by trying to use Western experience to reduce backlog.

The first such project in 2009 was "".

This is a German high-speed train Siemens Velaro, adapted for Russian conditions (gauge, weather conditions, etc.) All 16 trains in operation today were built in Germany - in fact, Russia simply purchased the trains. The project caused a lot of controversy and discussion, but as for me it was a very positive experience: constant and intensive commercial operation of high-speed trains began (Siemens Velaro is essentially a high-speed series, but for a number of reasons, which are discussed below, for now it is all high-speed train and Saspan's design speed of 250 km/h are not yet in use).

However, the 4 hours it takes to travel from Moscow to St. Petersburg on Sapsan is in fact faster than the same journey by plane. Yes, the plane flies faster, but due to the peculiarities of the infrastructure (you need to get from the city center to the airport, check in for the flight, wait for the flight, taxi, take-off, landing, back to the city), a train going from center to center here gives a significant gain in time and convenience . In a word, despite active criticism, the project took off.

Almost simultaneously with Sapsan, a similar Russian-Finnish project was launched -. There are already Italian trains Alstom Pendolino and the route St. Petersburg - Helsinki. In general, it is not as popular as Sapsan, but again, it has found its niche and is enjoying some success. Allegro again falls into the class of high-speed trains (407 km in 3 hours 27 minutes).

Since we’re talking about high-speed trains, it wouldn’t be out of place to mention - again, a German development for Russian roads (Siemens Desiro), but if Sapsan were simply purchased, here the trains were purchased with the possibility of local production - now a batch for the Moscow Central Circle is being made at the plant Ural Locomotives with a high percentage of localization.

In general, Swallows are used not only for suburban transport, but also on short intercity routes. The same train traveled from Moscow to St. Petersburg in a little more than five hours, and on other routes it fits into the concept of a “high-speed train.”

Well, of course, high-speed trains are not necessarily multi-unit trains. So let’s say the famous “Nevsky Express” (and before it “Aurora”) is an ordinary train (locomotive + unmotorized carriages, albeit very comfortable), which, however, due to the fast electric locomotive (previously there were ChS200, now EP20) takes 650 to travel kilometers a little more than four hours - a little less than the high-speed Sapsan.

So, for the transition from high-speed to high-speed trains, the trains themselves are not enough. A railway is generally a very complex infrastructure (rails and substrates/embankments for them, contact networks, signaling systems, etc.)

As it turned out during operation, Sapsan, although it can reach a speed of 250 km/h in some sections, but even taking into account all the improvements and modernizations of the road, it cannot go the entire way at that speed (and even more so even faster). Features of the contact network, turning radii, etc. Therefore, at the moment we have what we have as Sapsan, especially since Allegro, with all its excellent speed characteristics, is forced to go much slower than its capabilities (Allegro is generally forced to slow down to 30-40 km/h somewhere on winding roads). And one more problem - since the main line along which the trains move is common (all passenger and freight trains go on the same tracks), then when priority is given to high-speed trains, the remaining trains are forced to stand idle. I constantly travel to St. Petersburg by train No. 047 (Astrakhan - St. Petersburg) and it stops near St. Petersburg for more than an hour, “passing” Sapsan.

In general, the Moscow-Kazan high-speed highway project (via the cities of Vladimir, Nizhny Novgorod and Cheboksary) first of all implies the construction of a separate highway of a new type - nothing like this has ever been done in Russia (it is already clear that Chinese experience will be used - the Chinese are now generally leaders in world on high-speed rail construction). Of course, there will be special trains for this line with the ability to reach speeds of 300-400 km/h, still unknown - I assume that since Germany has also joined the project, with a high degree of probability we can say that this will be the next incarnation of Siemens Velaro. However, now one of the requirements is already known for sure - the production of trains for high-speed lines from start to finish in Russia, design with the participation of Russian engineers and a high percentage of localization - yes, this is not yet a completely own project, but this is a gradual catching up, and then we will see how will develop...

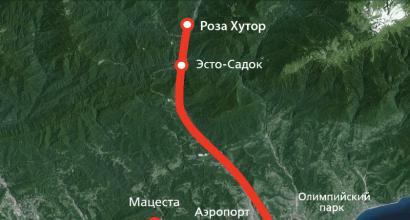

(the map that caught my eye is no longer relevant, the dates have been shifted, but the approximate direction of development can be assessed):

Well, at the same time, a few words about freight trains and their speeds. Of course, there are no longer any MPVs here - traction locomotives and a bunch of cars (80-120 cars in a train is the norm). When indicating the characteristics of locomotives, the same characteristics are found - design speed, long-duty speed (for the most popular VL80 on the Volga Railway, these figures are 110 km/h and 56 km/h, respectively). Since passenger trains have priority when moving along the railway, freight trains spend a lot of time at stops and sorting stations - waiting for their turn to move on.

It’s difficult to find real numbers, but a couple of years ago (I don’t think the situation has changed significantly now) I came across the following quote:

The average route speed of regular freight trains in Russia now exceeds 630 kilometers per day, container trains - about 900 kilometers, and these figures are growing at a rate of 3 percent per month. On the Trans-Siberian Railway, the speed of freight trains exceeds 1,120 kilometers per day, and this figure is growing at a rate of 7 percent per year.

At the same time, in terms of freight traffic, Russia ranks second in the world after China and is twice as fast as the United States, where, by the way, there is practically no passenger rail transportation. In such rather difficult conditions, the local speed of freight trains in Russia is 9 percent higher than in the United States and 10 percent higher than in China.

As we see, even on the most demonstrative sections, freight trains do not yet even approach the speeds of fast passenger trains (although they are already approaching). Meanwhile, such indicators are very good even by world standards. So you shouldn’t be surprised at the overwhelming majority of old freight locomotives - they are coping with their task so far (and now, apparently, a consistent replacement with new ones is beginning). We are clearly not in danger of switching to high-speed freight routes in the coming decades!

The fastest trains in Russia and the USSR

Russia is not a country with the fastest railways, and we are still very far from Japanese and French supertrains, but this was not always the case and in our country there have always been attempts to create our own high-speed trains, and a sufficient number of locomotives and trains have been created whose high-speed the characteristics are far from being so bad, and in their class they are not inferior to their foreign counterparts. Our rating contains only Russian or Soviet-made trains created at domestic factories. You can say that without Sapsan and Allegro this is not a rating, but it is a shame for us in a country like Russia to look with our mouths open at our neighbors and buy from them, and not create our own, so the rating will be exclusively from domestic trains.

I will not claim 100% reliability, but will build my rating based on available data, because there are many myths about the acceleration of this or that locomotive, but as usual there is a lack of documentary evidence. And so let's begin our top ten fastest Russian and Soviet trains.

TEP70

TEP70 is in tenth place in our ranking. This locomotive is the main diesel workhorse in passenger transportation on Russian Railways. The basic design of the diesel locomotive is so successful that it can be accelerated to very high speeds, but the design maximum speed is 160 km/h. There is no doubt that the locomotive is capable of reaching high speeds, and there were even rumors that it was accelerated to 220 km/h in tests, but the long-term speed is only 50 km/h, which does not allow us to place it higher in our rating. The diesel locomotive began operation in 1973, and its improved modification TEP70BS is currently being produced. It is produced at the Kolomna plant, and to date there are 300 of these machines and another 25 TEP70U driving around Russia.

In fact, there are plenty of locomotives with a design speed of 160 km/h in Russia, but this is the only diesel engine with such indicators, and it is also so widely produced, which is why it deserves its place.

"Martin"

Of course, it would be hard to call the Lastochka a purely Russian train, but it is the next one on our list of the fastest Russian trains. The main contribution to the creation was made by the same Siemens. The one who brought the Peregrine Falcons to Russia. Essentially, these trains are Siemens Desiro localized for our conditions. These locomotives are assembled at the Ural Locomotives plant, located in the city of Verkhnyaya Pyshma. The maximum design speed of a swallow is 160 km/h, but in fact the actual speed is somewhat lower, however, such trains are simply ideal for Russian roads, because often we simply have nowhere to accelerate faster. The main purpose is suburban or intercity transportation over short distances up to 200 km. At the moment, 46 ES2G trains have already been produced.

EP2K

EP2K is perhaps the most long-awaited locomotive of our time. In the USSR, this niche was successfully occupied by Czechoslovak emergency units of various models, and Soviet factories did not really strive to compete with them, and thus for a long time we had practically no high-speed passenger locomotives of our own production on electric traction. At the turn of the century, the first similar models began to appear in our country, however, they were all either slower, such as EP1, or, on the contrary, faster, but something completely different was required, namely the replacement of Czech emergencies. This task was successfully completed at the Kolomensky plant and in 2008 the EP2K went into production. The maximum operating speed is 160 km/h, but the locomotive can easily go faster, and the continuous speed is 90 km/h. At the moment, more than 300 EP2K locomotives have already been produced and in the future they should completely replace ChS 7.

"Oriole"

In 2014, the Tver Carriage Works presented its newest train, which was named EG2Tv Ivolga. The design speed of the train is 160 km/h, but Russian Railways made it clear that this is not exactly what was expected from the plant. For such speeds they are already producing the Lastochka, and the Oriole needs to be “accelerated”. There are rumors that during testing, a train consisting of three motor cars was accelerated to 250 km/h on a straight section, but this has not been documented anywhere, and the full train does not yet produce such a speed. At the moment, it is on the basis of the Ivolga that a passenger train is being created that can accelerate to 250 km/h, and time will tell whether Tverskoy Vagonostroitelny will be able to accomplish this task, but for now two trains have been built, which from 2017 will be tested on the Kiev direction of the Moscow Railway.

Steam locomotive type 2-3-2

The beginning of the 20th century was marked by a real boom in speed records in a variety of industries. Planes, cars, steam locomotives - all this moved faster and faster, and new records were set almost every year, and every developed country sought to join the elite by having high-speed transport. The Soviet Union did not lag behind in this direction, especially considering our distances. In 1936, the first project of the 2-3-2k steam locomotive of the Kolomna Plant appeared, which developed a power of 3070 hp, which allowed it to accelerate to 150 km/h. Through modification, the maximum speed increased to 170 km/h. The locomotive was successfully tested and showed excellent results, but the outbreak of war did not allow serial production of the model. At the same time, the Voroshilovgrad Plant also worked on improving the steam locomotive, and created a slightly faster model under the number 2-3-2B, which had a design speed of 180 km/h. He set his last record in 1957, when he reached a speed of 175 km/h.

EP20

Ep200

The top three fastest domestic trains opens with the experimental locomotive EP200, built at the Kolomensky Zavod in 1996. The EP200 appeared at an extremely unfortunate time, when it seemed to be very much needed, but there was no money for its creation, testing and modification. The design speed of the locomotive was 250 km/h, but in operation the speed was limited to 200 kilometers. There is no exact data on the maximum speed during testing.

For all its high-speed advantages, it was not destined to go on regular flights. At first, the EP200 did not shine with reliability, especially at high speeds. And after eliminating the shortcomings, it was never accepted, and in 2009 it was finally written off with the wording “Russian Railways does not need electric locomotives of this type,” which looks not just strange, but simply like direct sabotage in favor of the German Sapsan, since it was precisely its competitor, especially since on the basis of the EP200 the development of the EP250 and EP300 was already in full swing, the operating speed of which was supposed to be 250 and 300 km/h, respectively. After all the misadventures with the locomotive, the Kolomensky Plant focused on the production and improvement of TEP70 and EP2k. Perhaps in the near future we will still see high-speed locomotives and trains that will leave the gates of the Kolomna plant, but it will not be EP200.

Falcon 250

The fate of this train was no less sad than the EP200. The technical requirements for the development of a new train for high-speed transportation were ready in 1993. The leading development company was the Central Design Bureau for MT "RUBIN". Sokol 250 went to its first tests in 1998, during which everything possible was tested, and the train itself reached a maximum speed of 236 km/h, while its design speed was 250 km/h. During the tests, quite a few different but correctable shortcomings were found, and in fact the train was 90% ready. However, for unknown reasons, the project was canceled and the Falcon was sent to a museum. In fact, along with this locomotive, all the developments in creating such high-speed trains were ditched, and if we now try to do the same thing, we will have to start virtually from scratch again.

TEP 80

Ahead of its time - this is exactly what they said about the fastest Russian locomotive. It’s funny to say, but the fastest locomotive in Russia is not an electric locomotive, but a diesel locomotive TEP-80. When it was created, the TEP 70 was taken as a basis, which was not so fast, but had excellent potential for development. TEP 80 was equipped with a one and a half times more powerful engine with a capacity of 6000 hp, and it was this engine that allowed the locomotive to accelerate during testing to a record speed for Russia of 271 km/h. By the way, this record has not been broken by more than one diesel locomotive in the world to this day.

It was manufactured at the Kolomensky Plant in 1988-89, but the chaos in the country of the Soviets was not conducive to such breakthrough developments. The tests were carried out by the plant, and with the collapse of the union, no one needed the diesel locomotive at all. The speed record was set in 1993 and recorded on camera. Why this project has not yet been restored remains a mystery, but it has gone into oblivion just like Sokol and EP200 and is gathering dust in a museum, never going on regular flights, although our railways still need such locomotives, but If necessary, it will have to be built from scratch.

Trains are in a hurry, but not at all to the dustbin of history - on the contrary, every year they become more convenient, quieter and faster. Viewers of the Discovery Channel will be able to learn about how modern public transport is maintained in the “Mega Pit Stops” project, which airs on Saturdays at 11:00 (one of the episodes of the project is dedicated to the Russian “Sapsan” - you can watch it on May 18 ), and “Popular Mechanics” will tell about the history of the highest speed trains on the planet.

Editorial PM

Express and high speed

The concept of “high-speed train” does not have a generally accepted definition: it is usually said about railway transport, whose speed is on average higher than that of traditional trains: for example, in Russia, trains that reach speeds of 140 km/h and above are recognized as high-speed, and in India In Canada, this threshold is 160 km/h. But with the definition of “high-speed train” everything is much simpler: as a rule, this is the name given to all railway vehicles that can exceed the 200 km/h mark.

By the way, this threshold was taken at the beginning of the twentieth century by an experimental electric car from Siemens & Halske in October 1903, and just three weeks later the electric car from AEG already demonstrated a speed of 210.2 km/h. The first high-speed line (or HSR for short) appeared only in 1964 - it was the Japanese Tokaido Shinkansen line with a length of 515.4 km. The route quickly gained popularity and the costs of building the line were recouped in just seven years. The success of Japan contributed to the development of high-speed rail in many countries, and it continues to this day, and modern high-speed trains are direct confirmation of this.

Japan: Shinkansen trains

Although the name "Shinkansen" is translated from Japanese as "new highway", these trains are more often colloquially called "bullet trains": largely due to their impressive speed - many models have a design speed exceeding 300 km/h - and partly due to appearance of the zero series, which became a symbol of the Shinkansen.

The Shinkansen Series 0 electric trains were the first vehicles to enter service on the Tokaido Shinkansen Line in 1964. The line was electrified with single-phase alternating current 25 kV with a frequency of 60 Hz, and the wheel sets of all cars were powered by 185 kW traction motors, which provided a maximum speed of 210 km/h (in 1986 it was increased to 220 km/h). This line was built with a 1435 mm gauge, wider than the rest of the network (1067 mm). Thus, it cannot be used for freight transport or for trains other than shinkansen. The very first representatives of the series included 12, less often 16, cars; after a while they were joined by four- and six-car versions.

In 1982, the next series of electric trains on the Shinkansen network, number 200, entered service (curiously, the 100 series was launched only three years later - the fact is that shinkansen running east of the capital were given numbers of odd hundreds, and to the west - even numbers ): within its framework, modernized trains were later released with speeds from 240 to 275 km/h. In general, over all these years, about 20 different series of these trains have been developed, each of which is distinguished by its original design, number of cars, as well as design and technical features. For example, in the 300 series trains, DC electric motors were first replaced by three-phase AC traction motors; the 400 series trains have a narrower body, this is due to the fact that the high-speed line on which they ran was converted from a regular railway line, in the 500 series the maximum service speed of 300 km/h was achieved for the first time, the N700 series was the first to achieve acceleration of 0.722 m/s² among passenger shinkansen, and the E1 and E4 series trains each have two floors.

Shinkansen do not stop developing: in May of this year, the country introduced a new high-speed train Alfa-X, which can accelerate to 360 km/h (this is a record for passenger shinkansen). Its most striking feature is its 22-meter nose, designed to reduce air resistance, which especially increases when such a train enters tunnel sections at high speed. In addition, among the technical features of the series are air brakes and special magnetic plates in the braking system.

Japan: Maglev L0

In addition to high-speed passenger trains, Japan has been experimenting with the development of trains based on the principle of magnetic levitation (maglev for short) since the seventies of the last century. The essence of this technology is that trains move and are controlled by the forces of an electromagnetic field, without touching the surface of the rail during movement - this eliminates friction, thereby increasing the speed of movement.

Since 1972, about 10 different series of maglevs have been created in Japan, and one of the samples of the L0 series, presented to the public in 2012, during tests in 2015 accelerated to 603 km/h, setting an absolute speed record for railway transport (and land passenger transport). transport in general). In 2020, the country is going to release an improved L0 series, which will receive power from the guide path through electromagnetic induction.

It should be noted that so far Japanese maglevs are participating exclusively in experimental launches, but five years ago the country began to build the Chuo Shinkansen maglev line, which will run from Tokyo to Nagoya - the opening of the line is planned for the mid-twenties, and by 2045 they are going to complete it to Osaka.

China: Shanghai Maglev

Today, China ranks first in the world in terms of the length of high-speed railways: by the end of last year, their length reached 29 thousand km - this is approximately two-thirds of the total length of all high-speed railways in the world put into commercial operation - and in 2025 the local the government plans to increase this figure to 38 thousand km. One of the key completed projects in the field of high-speed rail transport is the Shanghai Maglev: the world's fastest magnetic levitation train in commercial operation (speeds up to 431 km/h) and the maglev line of the same name, 30 km long, connecting the Shanghai Longyang metro station Lu and Pudong International Airport. To cover this distance, the train takes only 7 minutes 20 seconds (depending on the train model, the time may increase by 50 seconds).

This ambitious and cutting-edge project, which cost China more than $1 billion, began commercial operation back in 2002, but even today it is still not profitable (annual losses amount to about $93 million). From the very beginning, the Shanghai Maglev was planned not as a viable market solution for the needs of travelers, but as a test project, on the basis of which it was planned to further develop China's railway infrastructure (it appeared before the massive creation of the HSR network in the country), but this idea was later abandoned for several reasons. “Firstly, the construction of such a line itself is extremely expensive. Secondly, from a technical point of view, it is very difficult to build it in real terrain conditions - this requires great technical research and a high engineering level in the country as a whole. Thirdly, maglev is incredibly difficult and expensive to maintain in operation, especially in conditions where the line is long: if the tracks sag for some reason, in the case of conventional and even high-speed railways they can be relatively easily straightened, but in the case of with maglev, when the line is supported by a million supports, it becomes very difficult,” explains Pavel Zyuzin, senior researcher at the Center for Research on Transport Problems of Megacities and the Institute of Transport Economics and Transport Policy at the Higher School of Economics. — If, for example, Japan can afford this - there are about 100 million inhabitants concentrated along a narrow strip of settlement between Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka, forming a corridor with extremely high demand - then this option is not suitable for China. At the same time, recently one of the metro lines there started operating using maglev technology - in this niche in China, magnetic levitation is completely justified and promising.” In general, despite many limiting factors, the expert considers maglev technologies to be the next stage in the development of high-speed rail, while “conventional” high-speed rail transport, in his opinion, has by and large reached the limits of its possible development.

France: TGV series trains

In response to the success of Japan's Shinkansen in the second half of the 20th century, France began building its high-speed trains, the TGV (French for Train à Grande Vitesse). At first, the developers were going to equip the designed trains with gas turbine engines, then with gas engines (this is exactly what the first prototype TGV 001, which appeared in 1972, had - by the way, it managed to set a world speed record among trains without electric traction at 318 km/h). However, due to increased fuel consumption, in the end this idea was also abandoned, and it was decided to build electric trains powered by a contact network. The all-electric Zébulon prototype was completed in 1974, and shortly thereafter the production of the TGV series models and the construction of the LGV lines dedicated to them began, which stands for Ligne à Grande Vitesse, and translates as “high-speed line”.

The first generation TGVs of the Sud-Est series began operating on the first LGV line in 1980 - their initial design speed was 270 km/h, although some of these trains later raised this figure to 300 km/h. The TGV Sud-Est was followed by other train series: TGV La Poste, TGV Atlantique, TGV Réseau, TGV Duplex and Euroduplex, as well as TGV TMST, TGV Thalys PBKA and TGV POS intended for international routes. The last of these series is famous for the world speed record for rail trains of 574.8 km/h, which the electric train TGV POS No. 4402 managed to set in 2007 - however, for this it was somewhat modernized: more powerful traction motors were installed in motor cars, thereby increasing increased the output power from 9.3 MW to 19.6 MW, equipped with wheelsets of larger diameter and closed the gaps between the cars for better streamlining.

The design process for the next generation of TGV, called Avelia Horizon, began in 2016. New features include greater capacity to carry up to 740 passengers, improved on-board services and communications, and a 20% reduction in energy consumption through the introduction of regenerative braking, which national rail carrier SNCF says makes the trains "the greenest TGVs yet" in history" (the latter is also supported by the fact that future trains, after decommissioning, can be 97% recycled). Last year, SNCF announced an order for hundreds of such trains, with deliveries due to begin in 2023.

Spain: Talgo 350

“Spain is the first country in Europe to build not a separate route, but an entire network of high-speed lines, which, given the presence of two central air hubs - Barcelona and Madrid - made travel around the country incredibly fast and, among other things, had a positive impact on the development tourism,” says Pavel Zyuzin. Today Spain ranks second in the world in terms of the length of the high-speed railway (2,850 km) - it is logical that high-tech trains run along them.

Talgo

Talgo

The AVE series 102 (or Talgo 350) trains, jointly produced by Talgo and Bombardier, running between Madrid and Barcelona are perhaps the most famous Spanish trains abroad. The Talgo 350 gained wide fame along with the nickname “Duck” largely due to its original and rather funny design: the nose of the train is elongated and actually somewhat resembles a duck’s - this was done to reduce aerodynamic drag.

In 1994, development of a prototype began. Initially, its creators set themselves the goal of achieving a design speed of 350 km/h (it’s not for nothing that this figure appears in the title), but in the end this figure was 330 km/h, which is due to the limitations of eight 1000 kW engines. But this speed is enough to cover the 621 km distance between Madrid and Barcelona in about 2 hours 30 minutes, if the train goes non-stop. In Spain, the AVE 102 series trains began running in 2007, and in 2011, Saudi Arabia signed a contract with Talgo to supply these trains to serve the then-project Haramain high-speed rail line between Mecca and Medina (the line itself opened in October last year). Taking into account the climatic and geographical characteristics of the region, as well as the wishes of customers, Talgo increased the number of seats due to the potentially high demand among pilgrims, increased the performance of the air conditioning system and took additional measures to protect the trains from sand and dust.

Russia: Sapsan

Among the most famous high-speed trains in the world is the international type, known in Russia as the Sapsan, which runs between Moscow and St. Petersburg. Among its distinctive features is the width of the train, which is 30 cm greater than the standard European one (this is due to the fact that Russia has a wider railway gauge), and in 2014, a double modification of the train of 20 cars was officially recognized as the longest high-speed train in the world. In addition, Sapsan was created using technologies adapted to the Russian climate: even if the temperature drops below -40°C, it can safely continue moving, whereas in warmer countries even light snow can paralyze railway traffic.

From the very beginning, Sapsan was conceived as a replacement for the high-speed trains ER200, which connected St. Petersburg and Moscow and which had become significantly outdated by the 2000s. In 2006, JSC Russian Railways entered into a contract with Siemens for the supply of eight high-speed trains based on the Velaro train, and already in 2009 the trains entered service. The version for Russia was named after the fastest bird in the world - the peregrine falcon, which can reach speeds of more than 322 km/h in a rapid diving flight. Technically, Sapsan also has the potential to overcome this milestone if there is appropriate separate infrastructure - for now its design speed is 250 km/h.

TRAIN SPEED

TRAIN SPEED

one of the most important indicators of the quality of operational work. S. d. p. is expressed by the number of kilometers traveled by a train during a unit of time (hour, day). There are four types of S.D.P.: a) chassis; b) tech. (distillation); c) district (commercial); d) route. Chassis S. d. p. - the average speed on a homogeneous section of track over a short period of time, during which there is no significant change in the speed of movement. This speed rarely remains the same for long periods of time, rising and falling as the track profile and traffic conditions change. The largest value of the chassis C d.p. called. maximum speed. Technical average speed is the average speed of movement on sections between two section stations, excluding train idle time at intermediate stations. Tech. S. d. p. is determined by dividing the distance traveled by the train by the time the train actually moves along the sections. Precinct S. d. p. called. the average speed between two section stations, taking into account the train's idle time at all intermediate stations. The district speed limit is determined by dividing the distance between two district stations by the total travel time of the train, including idle time at intermediate stations. Bringing the local railway station closer to the technical one by introducing a fixed schedule, reducing the time for stops and disseminating the experience of the best Stakhanovite drivers in non-stop and accelerated running of trains without collecting water at intermediate stations is the primary task of railway workers. tr-ta. Route S. d.p. - the average daily speed from the moment the route departs from the loading or formation station until the moment of arrival at the unloading or disbandment station, taking into account all stops at passing precinct and marshalling stations. The route distance within the limits of one road is calculated by the distance from the entrance to the exit point of the road, and for transit trains - between these points. S. d. p. for stages and sections is established train schedule. In order to ensure traffic safety, speed limit is limited: a) when driving along arrows onto deviated side tracks - no more than 40 km/h; b) when the train moves forward with cars - no more than 25 km/h; c) when accepting trains at dead-end stations - no more than 15 km/h; d) when passing a place fenced off with speed reduction signals - 25 km/h(unless a special warning is given indicating a different speed); e) when settling a train stopped on a steep slope - no more than 5 km/h; e) after departure from a faulty traffic light with a red light - no more than 15 km/h; g) when following trains - no higher than the speed of the train in front; h) when switching to manual due to damage to the auto brakes - no higher than the speed determined depending on the number of operating hand brakes.

Technical railway dictionary. - M.: State Transport Railway Publishing House. N. N. Vasiliev, O. N. Isaakyan, N. O. Roginsky, Ya. B. Smolyansky, V. A. Sokovich, T. S. Khachaturov. 1941 .

See what "TRAIN SPEED" is in other dictionaries:

The speed of trains is one of the most important indicators of railway performance. d. transport, expressing the number of kilometers traveled by a train per unit of time (usually an hour or day). There are structural, running, technical, sectional,... ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

It is usually measured in kilometers per hour, and in theoretical calculations in meters per second. Next to this actual speed of the train, the average or highest along the route, the commercial speed is often calculated, which is expressed as the average... ... Encyclopedic Dictionary F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Efron

maximum design speed of trains- Speed adopted for a given category of railway. Source: SP 119.13330.2012: 1520 mm gauge railways... Dictionary-reference book of terms of normative and technical documentation

Basic generalizing technology. a norm establishing the order of all work. d. iron law of transport operation (L. M. Kaganovich). The train schedule determines not only the movement of trains, but also the operation of locomotives, cars, stations, depots,... ... Technical railway dictionary

For the term "Graph" see other meanings. The train schedule is the organizing and technological basis for the work of all divisions of the railways, the plan for all operational work. Train movement is strictly on schedule... ... Wikipedia

Maximum permissible train speed- The maximum permissible speed is the speed of the train, which is allowed on the section according to the condition of the technical means (tracks, artificial structures, etc.) and is included in the train schedule. Maximum permissible speed... ... Official terminology

freight speed- The speed of trains with industrial goods when transporting them by rail. Conventionally: for small shipments 180 km, for wagon shipments 330 km, route shipments 550 km per day.… … Technical Translator's Guide

SPEED, CARGO- the speed of trains with industrial goods when transporting them by rail. Conventionally: for small shipments 180 km, for wagon shipments 330 km, route shipments 550 km per day... Great Accounting Dictionary

SPEED, HIGH- speed of trains when transporting perishable and other valuable goods. Conventionally: 330 km per day for small shipments of non-perishable goods and 660 km per day for perishable goods in refrigerated trains...

SPEED, CARGO- the speed of trains with industrial goods when transporting them by rail. Conventionally: for small shipments - 180 km, for wagon shipments - 330 km, route shipments - 550 km per day... Large economic dictionary

Books

- Instructions for the design, installation, maintenance and repair of continuous continuous track. Instructions for the installation, laying, maintenance and repair of continuous track have been developed taking into account the operational and climatic conditions of operation of continuous track, differentiation of the track according to...